I hear this at least once a week.

"She tries really hard but just doesn't have family support."

"Our XYZ students struggle because so many come from broken homes."

"There's not much you can do when he doesn't have a father at home."

When I was growing up I had many Uncles and Aunties. This Uncle was my dad's friend and this Auntie was really my mom's cousin and I'm not really sure how we knew that Auntie. Some of them were brothers and sisters of my parents. Some were cousins. Some were my parents' friends who were adults. All of them were family.

In the United States, when we think of family, we think of a father, a mother, and 2.5 kids.

When we look at our students, we see a missing father and think this kid doesn't have a family. We think a house with aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents is a sign of poverty. We look down on a mom with eight children and pity her assumed lack of education. We discount the woman who has taken care of all of the neighborhood kids.

Shift your lens for a moment. Imagine we valued an expanded view of family. The old woman who brings over food. The household full of noise and life and love. The neighbor who picks up all of the kids from school. Everyone becomes family. Now who has the deficit? The girl in this household who lacks a father but has the entire community? Or the boy with one sister, two parents, and doesn't know his neighbors?

We assign deficit to our students. There will always be a gap when we allow the ideal to be constructed using dominant norms.

Yes. The systems that imprison and deport the parents of our students need to be dismantled. I agree. But we make the problem worse.

That perceived deficit ends up having real-world consequences. We assume our student is misbehaving because he doesn't have a mother so we ignore it. We never call home because there's no father to call. We accept low scores because his mom has to work and isn't around to help.

We do nothing. We lower our expectations. We don't teach. Our students don't learn. A gap is created. It's not because your student doesn't have a father. It's because we missed the family he does have. To us, it just didn't look like family.

This doesn't stop with just schools and teachers. Invoking Patricia Hill-Collins, we can look at how transfer of wealth, loans, and taxation operate on an ideal of family that is centered on the dominant norm. We can look at our country built around freeways and the conveyances that fit a 2-partner, 2.5-child family so nicely. We can look at who can be a dependent on our health care and can visit us in prisons and hospitals. Even now, folks are becoming less comfortable with deporting a mother but are still fine with deporting the aunt who is the primary wage-earner in the household. Benefits accrue over time for those who fit the dominant norm of family, the system perpetuates itself, and gaps get wider. These systems stretch across our society yet are completely invisible.

We make the mistake of thinking we see deficits when we're really seeing differences. It is our obligation as teachers to de-center ourselves and see the strengths that are already in our students and our communities. Until this happens, we are part of the problem.

Always Formative

Assessment is a conversation.

Monday, March 24, 2014

Saturday, September 7, 2013

Between Silence and Silencing

Quick. Who is the foremost voice on the lives of the working poor?

.

.

.

.

.

Did you say Barbara Ehrenreich? I did. Truthfully, I couldn't come up with any other names.

This is a problem.

I appreciate the work of Barbara Ehrenreich. I do. Nobody has done more to bring the experiences of the working poor into the public discourse.

This is also a problem.

It is a problem that the voice for the working poor is not a voice of the working poor.

To say nothing allows our status quo to continue. By staying silent, the powerful maintain and benefit from the legacies of inequality.

But it is easy to pass from silence into silencing. Privilege amplifies voice. When those in power speak, it drowns out the voices of the marginalized.

We read Dr. Ehrenreich. We listen to Macklemore. We stop Kony. We celebrate V-Day.

The space between silence and silencing is difficult to navigate. It can't be done without intention. It is the smallest transition from speaking with to speaking for.

Dr. Ehrenreich should be writing books. Macklemore is entitled to make any music he wants.

However, along with acknowledging the role of our own privilege in making our voice heard, we need to use that privilege as a megaphone for the voices of the marginalized. Dr. Ehrenreich is in a position where she could publish an anthology written by the working poor. She could publicize or financially support Poor Magazine and the Poor News Network. It wouldn't take any effort for Macklemore to acknowledge other rappers that have confronted LGBT issues in hip-hop.

I recently watched the film Cracking the Codes: The System of Racial Inequity and it includes a scence where Dr. Joy DeGruy tells about a trip to the grocery store with her sister-in-law. The clip is on youtube.

I like this scene as an illustration of using privilege to amplify Dr. Joy DeGruy's voice. It is obvious that silence would have been the wrong tactic. Without the power of a privileged voice, it is quite likely the checker would have gotten more and more defensive. Her manager may have taken the checker's side. We see this all the time in school when a student may complain about a teacher and we close ranks around the teacher. Even if the situation was resolved, the checker may have gone home talking about the "angry Black woman" at the store.

On the other hand, the sister-in-law could have taken over. She could have re-centered the conversation around herself and away from Dr. DeGruy. She could have made the incident about her own favorite issue rather than the specific treatment of the checker towards Dr. DeGruy. The sister-in-law didn't attempt to put words in Dr. DeGruy's mouth or explicate the feelings of Dr. DeGruy. Her sister-in-law simply backed up Dr. DeGruy's statements and used her power to make sure Dr. DeGruy was heard.

It is a thin line. Sometimes I am too silent. Sometimes I'm too loud. When I'm silent it's because I don't notice or because I'm afraid to be noticed.

When I'm too loud it's because my own internalized hierarchies take over.

In many areas of my life I have power. I am a cis male. I am straight. I speak fluent English. I am educated and have never had to worry about when I will eat next.

The hardest thing to do isn't to turn up the volume so much that others are forced to listen. It is easy for me to be heard. The hardest thing to do is step aside and let others be heard in the space that I've been occupying.

------

1: I use "working poor" because that's the term used on Dr. Ehrenreich's website.

.

.

.

.

.

Did you say Barbara Ehrenreich? I did. Truthfully, I couldn't come up with any other names.

This is a problem.

I appreciate the work of Barbara Ehrenreich. I do. Nobody has done more to bring the experiences of the working poor into the public discourse.

This is also a problem.

It is a problem that the voice for the working poor is not a voice of the working poor.

To say nothing allows our status quo to continue. By staying silent, the powerful maintain and benefit from the legacies of inequality.

But it is easy to pass from silence into silencing. Privilege amplifies voice. When those in power speak, it drowns out the voices of the marginalized.

We read Dr. Ehrenreich. We listen to Macklemore. We stop Kony. We celebrate V-Day.

The space between silence and silencing is difficult to navigate. It can't be done without intention. It is the smallest transition from speaking with to speaking for.

Dr. Ehrenreich should be writing books. Macklemore is entitled to make any music he wants.

However, along with acknowledging the role of our own privilege in making our voice heard, we need to use that privilege as a megaphone for the voices of the marginalized. Dr. Ehrenreich is in a position where she could publish an anthology written by the working poor. She could publicize or financially support Poor Magazine and the Poor News Network. It wouldn't take any effort for Macklemore to acknowledge other rappers that have confronted LGBT issues in hip-hop.

I recently watched the film Cracking the Codes: The System of Racial Inequity and it includes a scence where Dr. Joy DeGruy tells about a trip to the grocery store with her sister-in-law. The clip is on youtube.

I like this scene as an illustration of using privilege to amplify Dr. Joy DeGruy's voice. It is obvious that silence would have been the wrong tactic. Without the power of a privileged voice, it is quite likely the checker would have gotten more and more defensive. Her manager may have taken the checker's side. We see this all the time in school when a student may complain about a teacher and we close ranks around the teacher. Even if the situation was resolved, the checker may have gone home talking about the "angry Black woman" at the store.

On the other hand, the sister-in-law could have taken over. She could have re-centered the conversation around herself and away from Dr. DeGruy. She could have made the incident about her own favorite issue rather than the specific treatment of the checker towards Dr. DeGruy. The sister-in-law didn't attempt to put words in Dr. DeGruy's mouth or explicate the feelings of Dr. DeGruy. Her sister-in-law simply backed up Dr. DeGruy's statements and used her power to make sure Dr. DeGruy was heard.

It is a thin line. Sometimes I am too silent. Sometimes I'm too loud. When I'm silent it's because I don't notice or because I'm afraid to be noticed.

When I'm too loud it's because my own internalized hierarchies take over.

In many areas of my life I have power. I am a cis male. I am straight. I speak fluent English. I am educated and have never had to worry about when I will eat next.

The hardest thing to do isn't to turn up the volume so much that others are forced to listen. It is easy for me to be heard. The hardest thing to do is step aside and let others be heard in the space that I've been occupying.

------

1: I use "working poor" because that's the term used on Dr. Ehrenreich's website.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

Supporting Teachers of Color

This is cross-posted at Educating Grace.

First, this post was co-written with Grace and heavily influenced by a post by Dr. Isis and one by Feminist Griote.

First, this post was co-written with Grace and heavily influenced by a post by Dr. Isis and one by Feminist Griote.

Second, we're writing about race in this post. To echo Feminist Griote, we're not trying to play Oppression Olympics. We're not here to argue who has it worse. We understand that different oppressions intersect and reinforce each other. However, we're using race as a center and, specifically, race in the United States.

Third, when we talk about racism, we don't usually mean, "Someone called me a name." What we're talking about is the broader internalized, structural, and institutional racism that permeates our schools like the smell of the cafeteria. And like that smell, it is its omnipresence that normalizes it. In most of the United States, we are less likely to be talking about overt racism as we are color-blind racism. Thus while it is important for all of us to address our own individual biases, it is our participation in a system of racist oppression that ultimately does the most damage.

The following are some Do's and Don’ts for supporting teachers of color.

1. Don't ask us to justify ourselves. To put a twist on the popular Hari Kondabolu quote, asking a teacher of color for evidence of racism is like asking a drowning person for evidence of water. Start with the assumption that racism exists.

Do acknowledge our experiences. We are not looking for approval and we are not looking for acceptance. What we do want is for you realize that we live in different realities. We have very different lived experiences and part of your acknowledgment is knowing that you can never really understand.

2. Don't expect us to educate you. We appreciate you asking. We really do. There are two things. First is from point 1. It often feels like we're not educating but rather defending. Two, it just gets tiring. It is like that kid in class who asks the most basic questions day in and day out and saying, "Look on the board" gets old.

Do educate yourself. We want you to be part of the conversation, but we need to get past the introductions. None of us will ever know everything. Education will be a constant. Do some basic googling. Read bell hooks. Some Omi and Winant. Learn about privilege and cultural wealth and stereotype threat. Start noticing the daily microaggressions and racial battle fatigue that we experience. Learn to check yourself anytime you want to mention the achievement gap or use exceptionals and majoritarian storytelling or the myth of hope. Once you get the basics down, we'll be happy to sit and have a conversation. This goes double for anything related to our specific race or ethnicity. Don't, for example, turn to us during Chinese New Year and ask what year it is. Seriously. Google. And please stop asking us where we're from. One of the main tenets of White privilege is that you don't have to think about racism or race. As an ally, it is your duty to start.

3. Don't make it about you. If there's one thing that's going to cause teachers of color to throw up their hands and walk away, it's re-centering the conversation. It is not time to talk about your own experiences with racism. Or how your grandmother said shocking things. Or how your own experience as an INSERT HERE makes you qualified to understand what we go through every day. We know that you're probably trying to connect our experiences with your own. But the consequence of this is often derailing the conversation and re-centering it on yourself. It can also feel defensive and lead us back to needing to justify ourselves.

Do seek out uncomfortable spaces. We need allies. Your voice is important but while racism is an issue for all of us, our experiences are uniquely our own. Challenge yourself by sharing in our discomfort. Until you've felt a sliver of our daily pain, we can't know that you aren't paying us lip service and then retreating to the blissful ignorance of color-blindness once our backs are turned. Only by sharing in our discomfort can we be sure that you are invested in creating a more just and equitable world.

4. Don't co-opt. Provide support, but we don't need you to solve our problems. We need you to solve your problems. You do you. We might have something we want to try. Let us try it. But don't jump in and offer "help" and suggestions. If you've reached point 2 and you've educated yourself, you know that your lived experiences in this world are completely different from ours. We will take the steps we think we need to take. At times, we may ask for some help, in which case, come in and then step back again.

Do the work on your end and we'll work ours. Racism needs to be fought from the side of the empowered and the side of the oppressed. Interrogate your privilege and then make every day a battle to fight it. Be prepared to be an ally, especially when you enter a space without any teachers of color. Call it out when you see it and help educate others in the White community. Closely examine the racial dynamics at play in your school. Whenever any systems in school re-create our social hierarchies, begin with the the assumption of racism and work from there

5. Don't enter our safe space. There are times when we just need a place to talk to each other. At the Institute, Jason reported actually feeling a physical change in his well-being. Sometimes we need that. We need to not worry about being judged because every one of us has held our tongues because we don't want to be the Angry Minority.

Do see yourself as having an important role. There are times when we need a safe place but if we're going to fight racism it will take all of us. There will be more times than not when we are working together. We may often be traveling different paths, but we are both heading towards the same destination.

6. Don't assume we have allies because there are other teachers of color on campus. So many teachers we talk to speak of feeling isolated even at schools with a high concentration of teachers of color. Conversations about race are difficult within communities of color as well and we aren't all in the same place when it comes to critical consciousness.

Do help create a safe environment. A campus racial climate survey might be a good way to get things rolling. Gather some data about participation (PTA, AP, remediation, extracurriculars) and talk about the results. Simply letting others know that you notice racism is a start. Being able to start a conversation about racism without worrying about being accused of being racist is part of your privilege. Use it for something positive.

Please continue this conversation in the comments. Which one of these most resonated with you? What will you do next? What have you seen other allies do that you’ve found supportive?

If you would like to comment anonymously, email Jason (jybuell - gmail) and he will add the comment himself.

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Community versus Conformity

This week I spent three days at the Institute for Teachers of Color Committed to Racial Justice (FB page). I'm still trying to process everything and decide what I can share.

The first session I attended was taught by the amazing Artnelson Concordia at Balboa High School in San Francisco. One of the things I learned about was his use of the unity clap and isang bagsak.

The UFW originated when the mostly Latin@ NFWA merged with the mostly Filipin@ AWOC. Meetings would start with unity clap to help bridge the language differences. Artnelson begins each of his classes with the unity clap.

Slides used with Artnelson's permission:

Isang bagsak literally means "one down." Someone shouts isang bagsak and everyone claps once simultaneously. Dalawang bagsak gets two claps. This started with the non-violent revolution in the Philippines to overthrow the Marcos regime and the idea is that if one falls, all of us fall.

Now compare Art's class to this Teaching Channel video on attention getters. If you click through the video is embedded, otherwise here's a direct link.

Listen to the words Nick Romagnolo uses. He talks about catching kids to see who is listening and of "programming" them.

If I walked into Art's class and the Nick's class these two practices would look identical. In both cases students are clapping and the end result is student attention. Despite that, these two practices could not be more different.

_____

Related: In Skills Practice, Christopher Danielson contrasted two videos of math teaching. A lot of the defense of the EDI video were comments about how the strategies themselves were good. My question is not about the strategies themselves but the intention of those strategies. Are they intended to honor the thinking of students? To create community? Or are they intended to ensure duplication?

The first session I attended was taught by the amazing Artnelson Concordia at Balboa High School in San Francisco. One of the things I learned about was his use of the unity clap and isang bagsak.

The UFW originated when the mostly Latin@ NFWA merged with the mostly Filipin@ AWOC. Meetings would start with unity clap to help bridge the language differences. Artnelson begins each of his classes with the unity clap.

Slides used with Artnelson's permission:

Isang bagsak literally means "one down." Someone shouts isang bagsak and everyone claps once simultaneously. Dalawang bagsak gets two claps. This started with the non-violent revolution in the Philippines to overthrow the Marcos regime and the idea is that if one falls, all of us fall.

Now compare Art's class to this Teaching Channel video on attention getters. If you click through the video is embedded, otherwise here's a direct link.

Listen to the words Nick Romagnolo uses. He talks about catching kids to see who is listening and of "programming" them.

If I walked into Art's class and the Nick's class these two practices would look identical. In both cases students are clapping and the end result is student attention. Despite that, these two practices could not be more different.

_____

Related: In Skills Practice, Christopher Danielson contrasted two videos of math teaching. A lot of the defense of the EDI video were comments about how the strategies themselves were good. My question is not about the strategies themselves but the intention of those strategies. Are they intended to honor the thinking of students? To create community? Or are they intended to ensure duplication?

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

End of Year Letter - 2013

This is one of those posts bloggers do to remind themselves of changes to make for next year. Nothing to see here. Move along.

At the end of the year one of the things I do is go to Target and buy 100s of Thank You cards. I think the pack I bought this year was $2.99 for 50. I ask students to write a thank you to a person at the school. It is usually a teacher but can be anyone. Our "student advisor" (AKA the huge guy that yanks kids out of class) gets a lot of cards as do the people that run the afterschool program. My only rule is that it can't be to me. Some kids do only one. I think this year one student wrote five. Then I drop them in mailboxes. It's a nice thing, especially for the 6th grade teachers who assume they have been forgotten.

I showed my students the Neil Tyson "Most Astounding Fact" video as the introduction and mentioned that this is where my introduction came from. Since I asked them to write Thank Yous yesterday I also included a thank you. Then I just gave them the letter. Like Sam, ideally I'd like students to keep it in their yearbook and randomly stumble on it every few years.

I tried to keep it to one page because I'm not entirely sure 8th graders will read even that much.

I over-edited and the transitions are ugly. I also took out the more personal stuff in favor of broader stuff. I think that was a mistake. I should have definitely left in, "Future classes will look up at the ceiling, see the smoke stains, and know that we were here."

At the end of the year one of the things I do is go to Target and buy 100s of Thank You cards. I think the pack I bought this year was $2.99 for 50. I ask students to write a thank you to a person at the school. It is usually a teacher but can be anyone. Our "student advisor" (AKA the huge guy that yanks kids out of class) gets a lot of cards as do the people that run the afterschool program. My only rule is that it can't be to me. Some kids do only one. I think this year one student wrote five. Then I drop them in mailboxes. It's a nice thing, especially for the 6th grade teachers who assume they have been forgotten.

I showed my students the Neil Tyson "Most Astounding Fact" video as the introduction and mentioned that this is where my introduction came from. Since I asked them to write Thank Yous yesterday I also included a thank you. Then I just gave them the letter. Like Sam, ideally I'd like students to keep it in their yearbook and randomly stumble on it every few years.

I tried to keep it to one page because I'm not entirely sure 8th graders will read even that much.

I over-edited and the transitions are ugly. I also took out the more personal stuff in favor of broader stuff. I think that was a mistake. I should have definitely left in, "Future classes will look up at the ceiling, see the smoke stains, and know that we were here."

Tuesday, May 7, 2013

Scientific Writing Scaffolds

As a department we've been working on different writing scaffolds. We use Constructing Meaning as a school which I think is mostly good. We've tried all kinds of different writing frames with varying degrees of success. Most of these come from Constructing Meaning. I'm going to take you in chronological order.

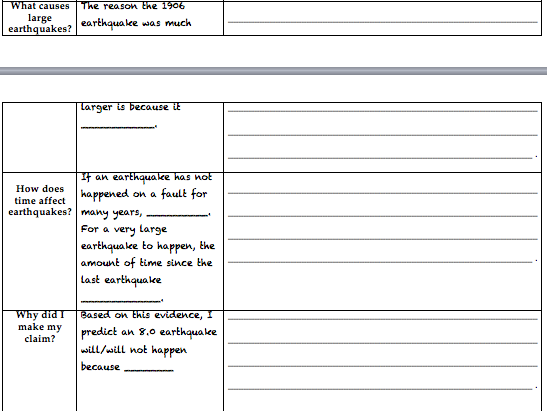

This was one of our first attempts.

It was our sixth graders' first or second try at extended science writing. The ease of entry here was very high. The downside is obviously that it is mostly fill in the blank. Except for the last frame there wasn't a lot of room to move. Also the writing itself is pretty clumsy.

We pulled two main lessons from this.

1. Start with a graphic organizer or build the template together. The tool made the writing process too invisible which is almost always a bad thing. The counterpoint to that argument is that we got the writing done first and then we could go back and deconstruct the setup. As a first attempt for the students, this might have been the way to go.

2. The academic support words were also too invisible. Constructing Meaning calls this the "mortar." We want students to gain flexibility with the mortar so they can use it on their own.

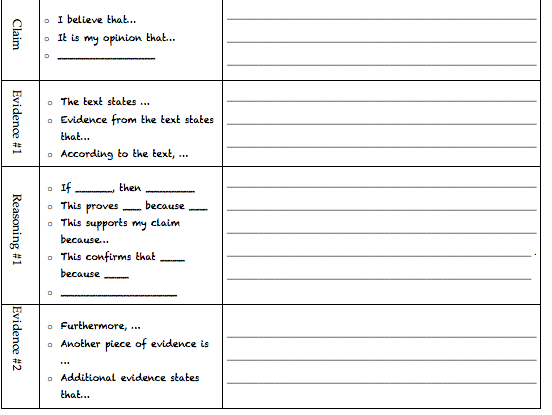

Next attempts:

This is just the first page but the back is similar. In this one we kept the headings on the side to highlight the purpose. We also pulled out the academic support words and gave them choices. This is probably our most used format. We've also been integrating in rebuttals so that's been very nice.

Below is an even more generalized example. The topic sentence is removed. The only things that change here are the word bank and perhaps some of the support words. I don't know what the topic was but the bio people can probably take a good guess.

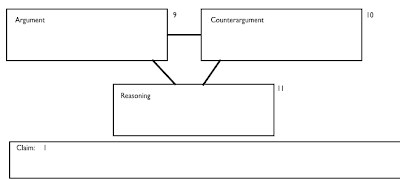

I put the claim at the bottom because I wanted them to go through each argument first before deciding on a claim. The numbers correspond to the sentence order in their final paper. I also provided about two dozen different sentence starters they could choose from (if needed). For example, "An argument in support of government provided flood insurance is_____. Others might respond that________. ___________ is more convincing because_______________."

Their claims I limited to "The government should/should not provide flood insurance." They could include a qualifying statement though such as, "The government should provide flood insurance but only if...."

I was very happy with the results here. It balanced structure and freedom pretty nicely. For this assignment we also engaged in a class debate first and students were able to gather arguments/counterarguments from the debate. In their papers, I asked them to cite other students as sources of arguments or counterarguments.

If there's anything I've gained from the last couple of years where I've focused on writing it's that speaking comes first. I can't stress that enough. Most of the tools above work just as well for speaking.

This was one of our first attempts.

It was our sixth graders' first or second try at extended science writing. The ease of entry here was very high. The downside is obviously that it is mostly fill in the blank. Except for the last frame there wasn't a lot of room to move. Also the writing itself is pretty clumsy.

We pulled two main lessons from this.

1. Start with a graphic organizer or build the template together. The tool made the writing process too invisible which is almost always a bad thing. The counterpoint to that argument is that we got the writing done first and then we could go back and deconstruct the setup. As a first attempt for the students, this might have been the way to go.

2. The academic support words were also too invisible. Constructing Meaning calls this the "mortar." We want students to gain flexibility with the mortar so they can use it on their own.

Next attempts:

This is just the first page but the back is similar. In this one we kept the headings on the side to highlight the purpose. We also pulled out the academic support words and gave them choices. This is probably our most used format. We've also been integrating in rebuttals so that's been very nice.

Below is an even more generalized example. The topic sentence is removed. The only things that change here are the word bank and perhaps some of the support words. I don't know what the topic was but the bio people can probably take a good guess.

We go back and forth about word banks. We've been happiest with "you can use all, some, or none of the words but if you're using all or none you're probably doing something wrong."

Most recently we gave all of our sixth graders a prompt from the textbook about whether or not the government should provide flood insurance. This came as part of a literacy unit we did where they read multiple articles with opposing viewpoints. The other sixth grade teacher and I approached it differently. Hers:

On my end, all they got was a graphic organizer. Below is the bottom portion. The rest was two more sets of the argument/counterargument/reasoning triangles. They provided an argument and counterargument and for the reasoning they wrote about which side was more convincing.

Their claims I limited to "The government should/should not provide flood insurance." They could include a qualifying statement though such as, "The government should provide flood insurance but only if...."

I was very happy with the results here. It balanced structure and freedom pretty nicely. For this assignment we also engaged in a class debate first and students were able to gather arguments/counterarguments from the debate. In their papers, I asked them to cite other students as sources of arguments or counterarguments.

If there's anything I've gained from the last couple of years where I've focused on writing it's that speaking comes first. I can't stress that enough. Most of the tools above work just as well for speaking.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Shuffle Quiz

We're in the midst of CST prep. I am bored. CST review is this weird game of picking out specific skills/topics not because they're important so much as they can be quickly recalled and practiced back to fluency.

Right now I'm leaning heavily on shuffle quizzes for my skills practice.

The basic idea is the students get a set of problems and work on them together. At spaced intervals a group member raises his/her hand and I come over. I take their papers and shuffle them up. Whoever gets their paper pulled gets asked the questions for the group. I ask the questions at the bottom and sign off when they can move on.

The only thing I did differently in these examples is that instead of everyone working the same problem, each member in a group of four was assigned a specific problem. (seat 1 did problem 1, seat 2 problem 2, etc). They split the big whiteboard into quarters and worked the problems. They took turns explaining and checking and then call me over. If this answers aren't correct I let them know and come back later. When they are working different problems I usually just ask for one problem to be explained but it's never their own.

Some use notes:

Here are some sample pics:

Notes: Graph A is the top right from this angle, Graph B is the top left, and Graph C is the bottom right. For the FBD scenario, we watched the clip on youtube earlier.

I don't know why speed-time graphs are so much more difficult for my students. I assume it's because I present position-time graphs first and they get locked in. Or maybe it's just easier to visualize changing position than changing speed. If you have any insights I'd love to hear them.

Right now I'm leaning heavily on shuffle quizzes for my skills practice.

The basic idea is the students get a set of problems and work on them together. At spaced intervals a group member raises his/her hand and I come over. I take their papers and shuffle them up. Whoever gets their paper pulled gets asked the questions for the group. I ask the questions at the bottom and sign off when they can move on.

The only thing I did differently in these examples is that instead of everyone working the same problem, each member in a group of four was assigned a specific problem. (seat 1 did problem 1, seat 2 problem 2, etc). They split the big whiteboard into quarters and worked the problems. They took turns explaining and checking and then call me over. If this answers aren't correct I let them know and come back later. When they are working different problems I usually just ask for one problem to be explained but it's never their own.

Some use notes:

- These questions are pretty plain vanilla to emulate the glory of the CST but I've used this strategy for more interesting questions. The more difficult the problem, the more students are assigned. When I went to see Complex Instruction at Mission HS, the teachers used this strategy for nearly all of the group work.

- It's a bit of an art to balance how many consecutive problems students should try before I need to be called over. Too many problems and students go too long without checking in. Too few and I can't sit with any one group long enough and other groups are just waiting around. For reference, my typical class is 8 groups of 4. For the density/Archimedes one the pacing ended up a bit quick but just barely. Next year I'd probably eliminate the first checkpoint because the first two sets are straight plug and chug but keep the last check point. For the graphing practice it was about right.

- Since this is review, I tried to cluster them into similar problem types.

- This year I used A/B/C/Redo but in previous years I've done a sign off with no score or plus/check/minus. I don't have a preference. Generally I just tell them I'll come back later if a student clearly isn't prepared.

- I've signed each paper and also just signed the one and had students staple them all together. Again, no preference.

Here are some sample pics:

Notes: Graph A is the top right from this angle, Graph B is the top left, and Graph C is the bottom right. For the FBD scenario, we watched the clip on youtube earlier.

I don't know why speed-time graphs are so much more difficult for my students. I assume it's because I present position-time graphs first and they get locked in. Or maybe it's just easier to visualize changing position than changing speed. If you have any insights I'd love to hear them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)